Individual member, and recently retired Alliance CEO, Jane Salmonson looks back on 2005’s Make Poverty History campaign and reflects on what we can learn from its successes and failures.

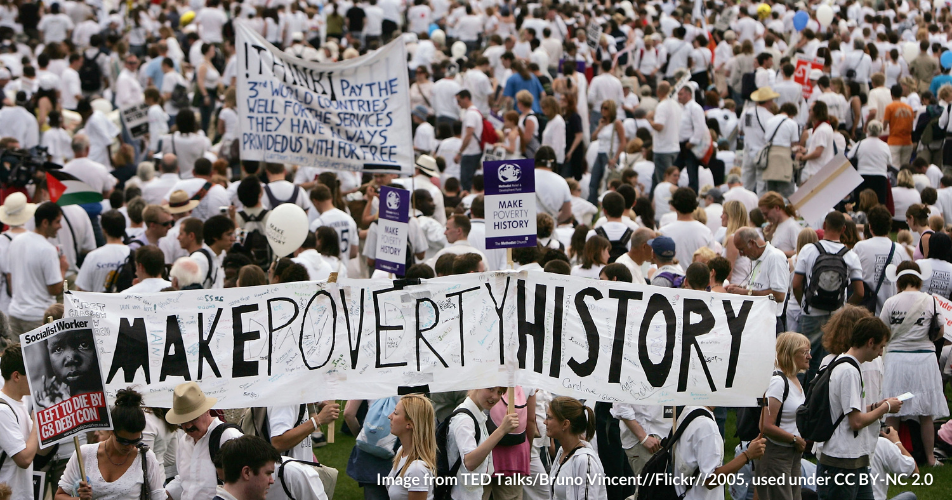

For those of us old enough to remember, the 2005 ‘Make Poverty History’ Campaign made a strong impact on public consciousness of global inequity. The campaign had its failings too and critics point to a one-dimensional portrayal of poverty. Leaving aside its rights and wrongs, it was extremely successful in mass mobilisation of public engagement.

‘Make Poverty History was all about people power’ wrote Oxfam in a 2015 article calling for renewed commitment ten years on. Thirty-six million people in over 70 countries joined the campaign which called for debt cancellation, more and better aid and trade justice. None of these issues were new in 2005. What was new was the mass movement to widen public awareness of them beyond development circles.

The campaign was a collaboration of over 500 NGOs and other civil society organisations. Large scale events were organised. Wrist bands were worn demonstrating belonging. A sense of common purpose was successfully generated.

Did the campaign make poverty history?

Probably not. The Brookings Institute’s 2011 Report Global Economy and Development points to a dramatic reduction in poverty worldwide since 2005, mostly emanating from economic growth in Asia, with Africa lagging behind. Causal links to the campaign would be hard to prove. However subsequent political events were probably the consequences of the mass show of public support. The G8 leaders in 2005 pledged $25bn for Africa, agreed debt cancellation for 40 low income countries and pledged funds for universal access to HIV/AIDs medication. In 2014 the commitment to allocate 0.7% of UK gross national income to official development assistance was enshrined into law. In 2015 the UK Government participated actively in the development of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and its pledge to ‘Leave No-One Behind.’

After 2015 the tide turned the other way. Neither the SDGs nor the Paris Agreement caught the public imagination or raised awareness much beyond pre-existing communities of interest. In 2016 the Brexit campaign stoked fears of being overwhelmed by immigrants – not helpful to stimulating a commitment to our common humanity. In 2018 public attention was indeed caught, but for the wrong reasons, by safeguarding scandals in the media. In 2020 Prime Minister Johnson announced the cutting of the UK’s aid budget from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income. There has been little opposition from the general public.

So where are we now?

The COVID-19 global pandemic has wrought widespread devastation through loss of life and damage to economies and livelihoods. Poverty and inequality are on the rise, so is early child marriage and gender based violence. At home, public attention has shifted from the international to the national, as we struggle with lost loved ones, lost jobs, education and personal freedoms.

Can the tide turn back again?

With only muted support from the voting public for international development, and public finances to rebuild, there seems to be little hope of that.

Perhaps we need mass mobilisation again, planned and conducted this time ‘with’ not ‘about’ low income countries, generating solidarity and demanding action in the face of the gravest global challenges yet which we all face together.